Testicular Cancer Ultrasound

The testicular ultrasound is one of our most common private ultrasounds in London for men to exclude testicular cancer which is a disease in where malignant (cancer) cells form in the tissues of one or both testicles.

The Testicles

The testicles are 2 egg-shaped glands located inside the scrotum (a sac of loose skin that lies directly below the penis). The testicles are held within the scrotum by the spermatic cord, which also contains the vas deferens and vessels and nerves of the testicles.

The testicles are the male sex glands and produce testosterone and sperm. Germ cells within the testicles produce immature sperm that travel through a network of tubules (tiny tubes) and larger tubes into the epididymis (a long coiled tube next to the testicles) where the sperm mature and are stored.

Almost all testicular cancers start in the germ cells. The two main types of testicular germ cell tumours are seminomas and nonseminomas. These 2 types grow and spread differently and are treated differently. Nonseminomas tend to grow and spread more quickly than seminomas. Seminomas are more sensitive to radiation. A testicular tumour that contains both seminoma and nonseminoma cells is treated as a nonseminoma.

Testicular cancer is the most common cancer in men 30 to 34 years old. There are 2400 testicular cases every year which is almost 6 every day.

Risk Factors of Testicular cancer

Anything that increases the chance of getting a disease is called a risk factor. Having a risk factor does not mean that you will get cancer; not having risk factors doesn't mean that you will not get cancer. People who think they may be at risk should discuss this with their doctor. Risk factors for testicular cancer include:

>

- Having had an undescended testicle.

- Having had abnormal development of the testicles.

- Having a personal or family history of testicular cancer.

- Being white.

Signs of testicular cancer.

Signs of testicular cancer include swelling or discomfort in the scrotum. These and other symptoms may be caused by testicular cancer. Other conditions may cause the same symptoms. A doctor should be consulted if any of the following problems occur:

- A painless lump or swelling in either testicle.

- A change in how the testicle feels.

- A dull ache in the lower abdomen or the groin.

- A sudden build-up of fluid in the scrotum.

- Pain or discomfort in a testicle or in the scrotum.

Diagnostic Tests

Tests that examine the testicles and blood are used to detect and diagnose testicular cancer.

The following tests and procedures may be used:

- Physical exam and history: An exam of the body to check general signs of health, including checking for signs of disease, such as lumps or anything else that seems unusual. The testicles will be examined to check for lumps, swelling, or pain. A history of the patient's health habits and past illnesses and treatments will also be taken.

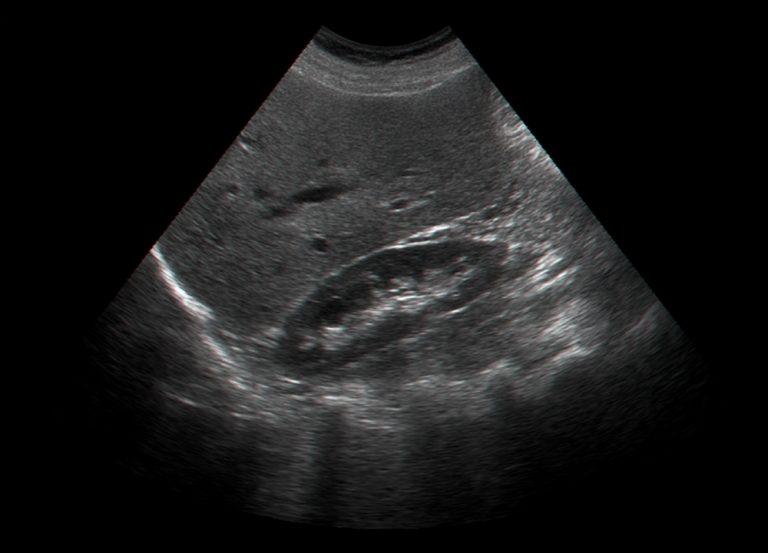

- Testicular Ultrasound exam: A procedure in which high-energy sound waves (ultrasound) are bounced off internal tissues or organs and make echoes.

You can read more about What is an Ultrasound Scan.

The echoes form a picture of body tissues called a sonogram. International Ultrasound Services provides testicular ultrasound scans and other private ultrasound tests helping to obtain a quick diagnosis and speed up any treatment. You can also combine your private scan with other ultrasound scans for men to evaluate your overall health. - Serum tumour marker test: A procedure in which a sample of blood is examined to measure the amounts of certain substances released into the blood by organs, tissues, or tumour cells in the body. Certain substances are linked to specific types of cancer when found in increased levels in the blood. These are called tumour markers. The following 3 tumour markers are used to detect testicular cancer:

- Alpha-fetoprotein (AFP).

- Beta-human chorionic gonadotropin (β-hCG).

- Lactate dehydrogenase (LDH). Tumour marker levels are measured before radical inguinal orchiectomy and biopsy, to help diagnose testicular cancer.

- Radical inguinal orchiectomy and biopsy: A procedure to remove the entire testicle through an incision in the groin. A tissue sample from the testicle is then viewed under a microscope to check for cancer cells. (The surgeon does not cut through the scrotum into the testicle to remove a sample of tissue for biopsy, because if cancer is present, this procedure could cause it to spread into the scrotum and lymph nodes.) If cancer is found, the cell type (seminoma or nonseminoma) is determined in order to help plan treatment.

Prognosis

The prognosis (chance of recovery) and treatment options depend on the following:

- Stage of cancer (whether it is in or near the testicle or has spread to other places in the body, and blood levels of AFP, β-hCG, and LDH).

- Type of cancer.

- Size of the tumour.

- Number and size of retroperitoneal lymph nodes.

Testicular cancer is often curable.

Treatment for testicular cancer can cause infertility.

Certain treatments for testicular cancer can cause infertility that may be permanent. Patients who may wish to have children should consider sperm banking before having treatment. Sperm banking is the process of freezing sperm and storing it for later use.

Stages of Testicular Cancer

After testicular cancer has been diagnosed, tests are done to find out if cancer cells have spread within the testicles or to other parts of the body.

The process used to find out if cancer has spread within the testicles or to other parts of the body is called staging. The information gathered from the staging process determines the stage of the disease. It is important to know the stage in order to plan treatment. The following tests and procedures may be used in the staging process:

•Chest x-ray: An x-ray of the organs and bones inside the chest. An x-ray is a type of energy beam that can go through the body and onto film, making a picture of areas inside the body.

•CT scan (CAT scan): A procedure that makes a series of detailed pictures of areas inside the body, taken from different angles. The pictures are made by a computer linked to an x-ray machine. A dye may be injected into a vein or swallowed to help the organs or tissues show up more clearly. This procedure is also called computed tomography, computerized tomography, or computerized axial tomography.

•Lymphangiography: A procedure used to x-ray the lymph system. A dye is injected into the lymph vessels in the feet. The dye travels upward through the lymph nodes and lymph vessels, and x-rays are taken to see if there are any blockages. This test helps find out whether cancer has spread to the lymph nodes.

•Abdominal lymph node dissection: A procedure to examine lymph nodes in the abdomen. Lymph nodes are removed and a pathologist checks them for cancer cells. For patients with nonseminoma, removing the lymph nodes may help stop the spread of disease. Cancer cells in the lymph nodes of seminoma patients can be treated with radiation therapy.

•Radical inguinal orchiectomy and biopsy: A procedure to remove the entire testicle through an incision in the groin. A tissue sample from the testicle is then viewed under a microscope to check for cancer cells. (The surgeon does not cut through the scrotum into the testicle to remove a sample of tissue for biopsy, because if cancer is present, this procedure could cause it to spread into the scrotum and lymph nodes.)

•Serum tumour marker test: A procedure in which a sample of blood is examined to measure the amounts of certain substances released into the blood by organs, tissues, or tumour cells in the body. Certain substances are linked to specific types of cancer when found in increased levels in the blood. These are called tumour markers. The following 3 tumour markers are used in staging testicular cancer:◦Alpha-fetoprotein (AFP)

◦Beta-human chorionic gonadotropin (β-hCG).

◦Lactate dehydrogenase (LDH).

Tumour marker levels are measured again, after radical inguinal orchiectomy and biopsy, in order to determine the stage of cancer. This helps to show if all of the cancer has been removed or if more treatment is needed. Tumour marker levels are also measured during follow-up as a way of checking if cancer has come back.

There are three ways that cancer spreads in the body.

The three ways that cancer spreads in the body are:

•Through tissue. Cancer invades the surrounding normal tissue.

•Through the lymph system. Cancer invades the lymph system and travels through the lymph vessels to other places in the body.

•Through the blood. Cancer invades the veins and capillaries and travels through the blood to other places in the body.

When cancer cells break away from the primary (original) tumour and travel through the lymph or blood to other places in the body, another (secondary) tumour may form. This process is called metastasis. The secondary (metastatic) tumour is the same type of cancer as the primary tumour. For example, if breast cancer spreads to the bones, the cancer cells in the bones are actually breast cancer cells. The disease is metastatic breast cancer, not bone cancer.

The following stages are used for testicular cancer: Stage 0 (Carcinoma in Situ)

In stage 0, abnormal cells are found in the tiny tubules where the sperm cells begin to develop. These abnormal cells may become cancer and spread into nearby normal tissue. All tumour marker levels are normal. Stage 0 is also called carcinoma in situ.

Stage I

In stage I, cancer has formed. Stage I is divided into stage IA, stage IB, and stage IS and is determined after a radical inguinal orchiectomy is done.

•In stage IA, cancer is in the testicle and epididymis and may have spread to the inner layer of the membrane surrounding the testicle. All tumour marker levels are normal.

•In stage IB, cancer:◦is in the testicle and the epididymis and has spread to the blood or lymph vessels in the testicle; or

◦has spread to the outer layer of the membrane surrounding the testicle, or

◦is in the spermatic cord or the scrotum and maybe in the blood or lymph vessels of the testicle.

All tumour marker levels are normal.

•In stage IS, cancer is found anywhere within the testicle, spermatic cord, or the scrotum and either:◦all tumour marker levels are slightly above normal; or

◦one or more tumour marker levels are moderately above normal or high.

Stage II

Stage II is divided into stage IIA, stage IIB, and stage IIC and is determined after a radical inguinal orchiectomy is done.

•In stage IIA, cancer:◦is anywhere within the testicle, spermatic cord, or scrotum; and

◦has spread to up to 5 lymph nodes in the abdomen, none larger than 2 centimetres.

All tumour marker levels are normal or slightly above normal.

•In stage IIB, cancer is anywhere within the testicle, spermatic cord, or scrotum; and either:◦has spread to up to 5 lymph nodes in the abdomen; at least one of the lymph nodes is larger than 2 centimetres, but none are larger than 5 centimetres; or

◦has spread to more than 5 lymph nodes; the lymph nodes are not larger than 5 centimetres.

All tumour markers levels are normal or slightly above normal.

•In stage IIC, cancer:◦is anywhere within the testicle, spermatic cord, or scrotum; and

◦has spread to a lymph node in the abdomen that is larger than 5 centimetres.

All tumour marker levels are normal or slightly above normal.

Stage III

Stage III is divided into stage IIIA, stage IIIB, and stage IIIC and is determined after a radical inguinal orchiectomy is done.

•In stage IIIA, cancer:◦is anywhere within the testicle, spermatic cord, or scrotum; and

◦may have spread to one or more lymph nodes in the abdomen; and

◦has spread to distant lymph nodes or to the lungs.

The level of one or more tumour markers may range from normal to slightly above normal.

•In stage IIIB, cancer:◦is anywhere within the testicle, spermatic cord, or scrotum; and

◦may have spread to one or more nearby or distant lymph nodes or to the lungs.

The level of one or more tumour markers may range from normal to high.

•In stage IIIC, cancer:◦is anywhere within the testicle, spermatic cord, or scrotum; and

◦may have spread to one or more nearby or distant lymph nodes or to the lungs or anywhere else in the body.

The level of one or more tumour markers may range from normal to very high.

Testicular Cancer Prognosis

For nonseminoma, all of the following must be true:

•The tumour is found only in the testicle or in the retroperitoneum (area outside or behind the abdominal wall); and

•The tumour has not spread to organs other than the lungs; and

•The levels of all the tumour markers are slightly above normal.

For seminoma, all of the following must be true:

•The tumour has not spread to organs other than the lungs; and

•The level of alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) is normal. Beta-human chorionic gonadotropin (β-hCG) and lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) may be at any level.

Intermediate Prognosis

For nonseminoma, all of the following must be true:

•The tumour is found in one testicle only or in the retroperitoneum (area outside or behind the abdominal wall); and

•The tumour has not spread to organs other than the lungs; and

•The level of any one of the tumour markers is more than slightly above normal.

For seminoma, all of the following must be true:

•The tumour has spread to organs other than the lungs; and

•The level of AFP is normal. β-hCG and LDH may be at any level.

Poor Prognosis

For nonseminoma, at least one of the following must be true:

•The tumour is in the centre of the chest between the lungs; or

•The tumour has spread to organs other than the lungs; or

•The level of any one of the tumour markers is high.

There is no poor prognosis grouping for seminoma testicular tumours.

Testicular Cancer Questions and Answers

•Nearly all testicular cancers are one of two general types: seminoma or nonseminoma. Other types are rare (see Question 1).

•This disease occurs most often in men between the ages of 20 and 39. It accounts for only 1 per cent of all cancers in men (see Question 1).

•Risk factors include having an undescended testicle, previous testicular cancer, and a family history of testicular cancer (see Question 2).

•Symptoms include a lump, swelling, or enlargement in the testicle; pain or discomfort in a testicle or in the scrotum; and/or an ache in the lower abdomen, back, or groin (see Question 3).

•Diagnosis generally involves blood tests, ultrasound, and biopsy (see Question 4).

•Treatment can often cure testicular cancer (see Question 5), but regular follow-up exams are extremely important (see Question 6).

1. What is testicular cancer?

Testicular cancer is a disease in which cells become malignant (cancerous) in one or both testicles.

The testicles (also called testes or gonads) are a pair of male sex glands. They produce and store sperm and are the main source of testosterone (male hormones) in men. These hormones control the development of the reproductive organs and other male physical characteristics. The testicles are located under the penis in a sac-like pouch called the scrotum.

Based on the characteristics of the cells in the tumour, testicular cancers are classified as seminomas or nonseminomas. Other types of cancer that arise in the testicles are rare and are not described here. Seminomas may be one of three types: classic, anaplastic, or spermatocytic. Types of nonseminomas include choriocarcinoma, embryonal carcinoma, teratoma, and yolk sac tumors. Testicular tumours may contain both seminoma and nonseminoma cells.

Testicular cancer accounts for only 1 per cent of all cancers in men in the United States. About 8,000 men are diagnosed with testicular cancer, and about 390 men die of this disease each year (1). Testicular cancer occurs most often in men between the ages of 20 and 39, and is the most common form of cancer in men between the ages of 15 and 34. It is most common in white men, especially those of Scandinavian descent. The testicular cancer rate has more than doubled among white men in the past 40 years but has only recently begun to increase among black men. The reason for the racial differences in incidence is not known.

1. What are the risk factors for testicular cancer?•Undescended testicle (cryptorchidism): Normally, the testicles descend from inside the abdomen into the scrotum before birth. The risk of testicular cancer is increased in males with a testicle that does not move down into the scrotum. This risk does not change even after surgery to move the testicle into the scrotum. The increased risk applies to both testicles.

•Congenital abnormalities: Men born with abnormalities of the testicles, penis, or kidneys, as well as those with inguinal hernia (hernia in the groin area, where the thigh meets the abdomen), may be at increased risk.

•History of testicular cancer: Men who have had testicular cancer are at increased risk of developing cancer in the other testicle.

•Family history of testicular cancer: The risk for testicular cancer is greater in men whose brother or father has had the disease.

The exact causes of testicular cancer are not known. However, studies have shown that several factors increase a man's chance of developing this disease.

1. How is testicular cancer detected? What are the symptoms of testicular cancer?•a painless lump or swelling in a testicle

•pain or discomfort in a testicle or in the scrotum

•any enlargement of a testicle or change in the way it feels

•a feeling of heaviness in the scrotum

•a dull ache in the lower abdomen, back, or groin

•a sudden collection of fluid in the scrotum

Most testicular cancers are found by men themselves. Also, doctors generally examine the testicles during routine physical exams. Between regular checkups, if a man notices anything unusual about his testicles, he should talk with his doctor. Men should see a doctor if they notice any of the following symptoms:

These symptoms can be caused by cancer or by other conditions. It is important to see a doctor to determine the cause of any of these symptoms.

1. How is testicular cancer diagnosed?

•Blood tests that measure the levels of tumour markers. Tumour markers are substances often found in higher-than-normal amounts when cancer is present. Tumour markers such as alpha-fetoprotein (AFP), Beta-human chorionic gonadotropin (ßHCG), and lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) may suggest the presence of a testicular tumour, even if it is too small to be detected by physical exams or imaging tests.

•Ultrasound, a test in which high-frequency sound waves are bounced off internal organs and tissues. Their echoes produce a picture called a sonogram. Ultrasound of the scrotum can show the presence and size of a mass in the testicle. It is also helpful in ruling out other conditions, such as swelling due to infection or a collection of fluid unrelated to cancer.

•Biopsy (microscopic examination of testicular tissue by a pathologist) to determine whether cancer is present. In nearly all cases of suspected cancer, the entire affected testicle is removed through an incision in the groin. This procedure is called radical inguinal orchiectomy. In rare cases (for example, when a man has only one testicle), the surgeon performs an inguinal biopsy, removing a sample of tissue from the testicle through an incision in the groin and proceeding with orchiectomy only if the pathologist finds cancer cells. (The surgeon does not cut through the scrotum to remove tissue. If the problem is cancer, this procedure could cause the disease to spread.)

To help find the cause of symptoms, the doctor evaluates a man's general health. The doctor also performs a physical exam and may order laboratory and diagnostic tests. These tests include:

If testicular cancer is found, more tests are needed to find out if cancer has spread from the testicle to other parts of the body. Determining the stage (extent) of the disease helps the doctor to plan appropriate treatment.

1. How is testicular cancer treated? What are the side effects of treatment?•Surgery to remove the testicle through an incision in the groin is called a radical inguinal orchiectomy. Men may be concerned that losing a testicle will affect their ability to have sexual intercourse or make them sterile (unable to produce children). However, a man with one healthy testicle can still have a normal erection and produce sperm. Therefore, an operation to remove one testicle does not make a man impotent (unable to have an erection) and seldom interferes with fertility (the ability to produce children). For cosmetic purposes, men can have a prosthesis (an artificial testicle) placed in the scrotum at the time of their orchiectomy or at any time afterwards.

Some of the lymph nodes located deep in the abdomen may also be removed (lymph node dissection). This type of surgery does not usually change a man's ability to have an erection or an orgasm, but it can cause problems with fertility if it interferes with ejaculation.

References:

NHS - Ultrasound Scan

FDA - Ultrasound Imaging

NHS- Ultrasound Scans in Pregnancy

NHS - 12-week scan

ROOG - Guidance for antenatal screening and ultrasound in pregnancy in the evolving coronavirus pandemic

NICE - Antenatal care for uncomplicated pregnancies

BMUS - Guidelines for the safe use of diagnostic ultrasound equipment

Ultrasound in Obstetrics and Gynaecology - ISUOG Practice Guidelines: performance of first‐trimester fetal ultrasound scan

Healthline - Pregnancy Ultrasound

WHO - WHO recommendation on early ultrasound in pregnancy

Medically Reviewed by Tareq Ismail Pg(Dip), BSc (Hons)