Breast cysts are fluid-filled sacs that form within the breast tissue. They're most common among women between 30-50 years of age and rarely occur after menopause.

These fluid-filled sacs are noncancerous (benign). They may develop as a result of normal hormonal changes in your breasts during your menstrual cycle.

Palpable Lumps

Breast lumps or cysts, which are defined as areas of firm or smooth tissue with borders distinct from surrounding breast tissues, can be felt as a lump on one or both breasts and typically go undetected. Cysts typically increase in size before and during your period but usually recede after it ends.

Breast tissue consists of glandular lobes that produce milk and are divided into smaller lobules. They are surrounded by fatty tissue and fibrous connective tissue. Women's breast glands remain active throughout their lives, changing in size and ratio of milk glands to fatty tissue as they age.

Women over 30 years of age commonly experience hormonal fluctuations during their menstrual cycle. While these effects typically disappear after menopause, some post-menopausal women taking hormone replacement therapy may still experience them.

However, a lump can be caused by many different things, including cancer. That is why it is essential to get an accurate diagnosis for any lump you feel in your breasts.

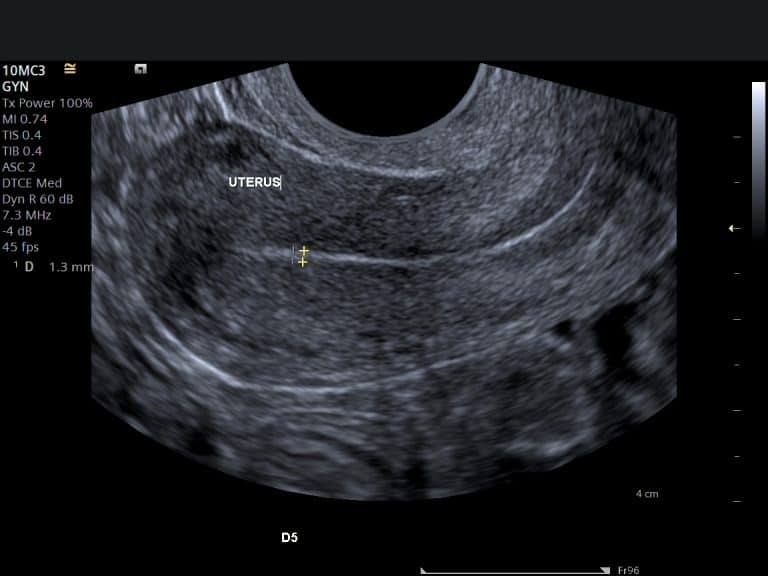

Ultrasound can identify the source and extent of your lump, as well as whether it's cancerous. It also provides information on its size and location.

A transducer, such as a microphone, is placed over the area of concern. Sound waves from this transducer bounce off different areas of breast tissue and create echoes which can be observed on a monitor.

Once your ultrasound images are acquired, you can view them immediately or save them for future reference. Ultrasound also provides insight into the condition and its spread.

Breast lumps and cysts are two types of benign (non-cancerous) changes to fibrous tissue or cysts that don't need treatment; the latter are more serious. Both conditions occur quite commonly among most women and should not cause concern unless you have a history of other medical problems which make you more vulnerable to developing cancer in the future.

Acoustic Enhancement

Ultrasound imaging uses sound waves to produce pictures of your body. It can help your doctor detect breast cysts and tumors and guide fine-needle aspiration to remove fluid.

Ultrasound imaging involves moving a handheld, wand-like instrument called a transducer over your skin surface and sending out sound waves. These vibrations pick up echoes from deep within your body tissues and produce pictures on a computer screen.

Sonographers can use various techniques to detect breast cysts, such as acoustic enhancement and E imaging (real time shear wave elastography). Acoustic enhancement is caused by decreased impedance, which is common in veins and cysts. It helps differentiate benign masses from cancerous lesions and improve the accuracy of ultrasound diagnosis.

A benign mass typically has a soft acoustic texture, distinguishing it from malignant tumors which are hard and difficult to see on ultrasound. Furthermore, elastography can demonstrate the hardness of a mass to help distinguish it from other types of breast lesions.

Studies have demonstrated that women with breast fibroadenomas tend to exhibit more acoustic shadowing than other lesions, especially those that have calcifications embedded in tissue [6, 8, 9]. Prevalent acoustic shadowing (PAS) is also more frequent among fibroadenomas than cancers; ultrasound serves as an invaluable diagnostic tool in both groups.

Posterior acoustic enhancement is often observed in hepatocellular carcinomas and may be indicative of either the cancer or liver itself. It can help detect these lesions more accurately, making screening for hepatocellular carcinoma among an increasingly large population with liver disease an important consideration.

Posterior acoustic enhancers are typically present in most TNBCs, making it difficult to differentiate them from benign neoplasms. Since TNBCs tend to be more malignant than fibroadenomas, more caution should be exercised during evaluation in order to avoid misdiagnosis or delayed treatment. A misdiagnosed TNBC can result in a poor prognosis with increased mortality rates.

Wall Thickness

If you feel a lump in your breast, your healthcare provider may recommend testing. Mammograms, ultrasounds or MRI (magnetic resonance imaging) can help determine the type of cyst you have.

Cysts are pockets filled with fluid, pus, air or other substances. While usually benign, cysts may develop into cancerous tumors if they grow rapidly or become large in size.

When someone feels a cyst on their breast, they may worry that it could lead to breast cancer in the future. However, studies have shown that having just a simple cyst does not increase your risk for developing breast cancer, so there's no need to fret.

One can tell the difference between a simple cyst and one with more complex characteristics by looking at its shape and size. Simple cysts have thin walls that look smooth, while complex ones often feature irregular borders and thick walls.

Wall thickness is another key factor used by doctors to differentiate between simple and complex cysts. A complex cyst typically features thick walls with numerous septations that divide up the fluid inside.

Additionally, complex cysts often contain solid material within them and sand-colored debris on their bottoms.

Women with complex cysts that grow rapidly might require a core needle biopsy (CNB). This test is essential in helping your healthcare team determine if the lump is cancerous.

Ultrasound is an invaluable tool for evaluating the walls of complex cysts, which may be difficult to see with mammograms or other tests. Additionally, it provides additional details about the mass such as its size and location.

The wall thickness of a simple cyst can range anywhere from 0.5 mm to 4 mm, which is ideal in most circumstances; however, in certain instances this range may change slightly.

Women with complex cysts may require a core needle biopsy or ultrasound-guided FNA (fine needle aspiration). This test is crucial as it can tell your healthcare team whether the cyst is cancerous or noncancerous.

Fluid Content

Breast cysts are fluid-filled sacs that form when the lining of a woman's breast grows faster than she can replace it, usually in older women. Although breast cysts can occur at any age, they tend to occur more frequently among older women.

Cysts typically measure less than one centimeter in diameter, but can grow larger. If they become large, it may feel like lumps on your skin. If you're concerned about what might be causing the lump, your doctor may order an imaging test to identify its source.

Ultrasound is highly accurate at sizing and characterizing breast cysts, as well as showing whether they are solid or filled with fluid.

The fluid within a cyst may vary in color and consistency, making it easy to distinguish it from surrounding tissue. Some fluids are clear, while others take on a straw-colored hue that makes it easier to identify where the mass lies.

If the cyst is causing you discomfort or pain, your doctor can drain the fluid from it to eliminate it. This procedure usually doesn't lead to any adverse effects.

A fine-needle aspiration is another way your doctor can determine if the lump in your breast is filled with fluid or solid matter. They will insert a thin needle into the cyst and attempt to extract (aspirate) any fluid present.

If the fluid is clear or straw-colored and nonbloody, then it's generally benign. On the contrary, bloody-looking fluids have an increased likelihood of being cancerous.

Your doctor may want to take a sample of the fluid from the cyst in order to check if it's cancerous. They can do this with either a needle biopsy or using a syringe.

The fluid from a breast cyst can be tested chemically to identify its composition. This testing, which is relatively new, helps your doctor diagnose the lump and decide if it's benign or cancerous.

Breast macrocysts are fluid-filled masses greater than 1 cm in diameter that may be abnormal development or involution and often associated with apocrine metaplasia. Although not typically malignant or recurring, they may cause discomfort.